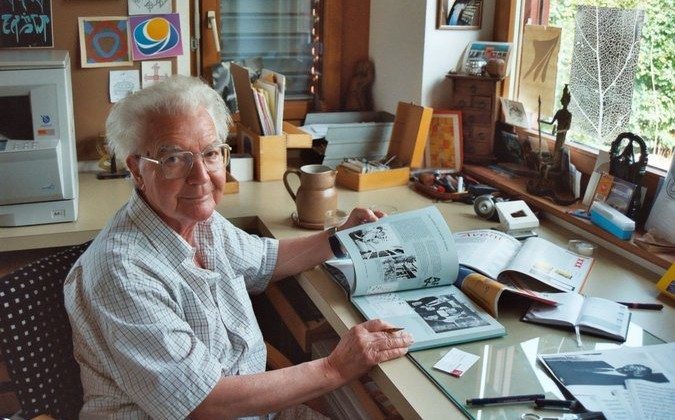

Adrian Frutiger Dies at 87; His Type Designs Show You the Way

For more than 50 years, Adrian Frutiger made the world legible.

A type designer who died on Sept. 10 at 87 in his native Switzerland, Mr. Frutiger created some of the most widely used fonts of the 20th century, seen daily in airports, on street signs and in subway stations around the world.

Mr. Frutiger, whose career spanned the era of hot lead and the age of silicon, created some 40 fonts, a vast number for one lifetime. Praised for an elegant readability that belied their rigorous engineering, his typefaces over the years have graced signs in the Paris Métro and many international airports, and on Swiss highways and some London streets.

His best-known fonts include Univers, employed throughout the design of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, and Frutiger, ubiquitous on airport signage, including that of John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York and Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris.

“Frutiger is basically the best signage type in the world because there’s not too much ‘noise’ in it, so it doesn’t call attention to itself,” Erik Spiekermann, a prominent German type designer and a longtime friend of Mr. Frutiger, said by telephone on Wednesday. “It makes itself invisible, but physically it’s actually incredibly legible.”

Photo: Marlene Awaad/Bloomberg

“That’s the one that’s on the bottom of all our checks,” Mr. Spiekermann said. “He managed to do something that is legible by machine and by people alike.”

A font is how the sounds of language meet the eye, and each character has its own anatomy, temperament and needs: You cannot simply toss 26 letters and 10 numbers into a caldron, give them a stir and have a font emerge.

A type designer is obliged to reconcile the often competing imperatives of form and function, for a font that is especially beautiful may not be especially legible, and vice versa. Postmodernity — in which words are read not only on paper but also on fleetingly glimpsed highway signs, computer screens and cellphones — has only amplified the problem.

The Romans never considered these contingencies when they adopted a version of the alphabet, handed down via the Greeks and Etruscans, that had been invented by the Phoenicians in about 1000 B.C. As a result, threats to legibility loom everywhere in the Roman alphabet’s present-day incarnation, as anyone who has ever read an eye chart knows.

Consider the following:

a, e, c, o, u.

Now move farther away from your screen or, if you are tradition-minded, from your morning newspaper. Consider the line again. The once-tractable letters have turned unruly and are now barely distinguishable one from another.

Thus, for the type designer, the creation of a new font entails much brooding at the drawing board over the architecture, proportion and slant of each character in a range of weights and sizes.

“A letter,” Mr. Frutiger told the English-language publication Swiss News in 2001, “follows the same canons of beauty as a face: A beautiful letter is in perfect proportion. The bar of a ‘t’ placed too high, the curve of an ‘a’ too low, are as jarring as a long nose or a short chin.”

Mr. Frutiger was known for paying special attention to the insides of letters — the negative space captured within an “o” or nestling in the crook of a “c.” Such space, he said, could be used profitably to demarcate one letter from another, or, for that matter, a capital “O” from the numeral 0.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

Univers, a typeface designed by Mr. Frutiger, on the sign for Downing Street. No. 10 is the office and home of the prime minister.

Though he was renowned for his sans serif typefaces — fonts lacking the small, hairlike strokes at the tops and bottoms of letters that help move the eye along — Mr. Frutiger bore no animus toward serif fonts; over time, he designed several. It is simply that he came of age professionally in the teeth of the sans serif era.

The son of a weaver, Adrian Johann Frutiger was born on May 24, 1928, in Unterseen, near Interlaken, Switzerland. As a youth he hoped to be a sculptor, but his father discouraged him from plying so insecure a trade. Apprenticed to a typesetter as a teenager, he found his life’s work.

In 1952, after graduating from the School of Applied Arts in Zurich, Mr. Frutiger moved to Paris, where he was a designer with the type foundry Deberny & Peignot, eventually becoming its artistic director. There he created some of his earliest fonts, among them Président, Méridien and Ondine; in the early 1960s he founded his own studio in Paris.

Commissioned to create signage for airports and subway systems, Mr. Frutiger soon realized that fonts that looked good in books did not work well on signs: The characters lacked enough air to be readable at a distance. The result, over time, was Frutiger, a sans serif font designed to be legible at many paces, and from many angles.

One of Frutiger’s hallmarks is the square dot over the lowercase “i.” The dot’s crisp, angled corners keep it from resolving into a nebulous flyspeck that appears to merge with its stem, making “i” look little different from “l” or “I.” (For designers of sans serif fonts, the gold standard is to make a far-off “Illinois” instantly readable.)

After four decades in Paris, Mr. Frutiger returned to Switzerland in the early 1990s. His death, in Bremgarten bei Bern, was announced by Linotype GmbH, a German typeface maker with which he was long associated.

Mr. Frutiger’s first wife, Paulette Flückiger, died in 1954 after giving birth to their son, Stéphane. Besides his son, Mr. Frutiger’s survivors include two brothers, Roland and Erich, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Mr. Frutiger married Simone Bickel in 1955; she died in 2008. Two daughters from their marriage, Anne-Sylvie and Annik, committed suicide as young women. With his wife, Mr. Frutiger established the Adrian and Simone Frutiger Foundation, which supports research in neuropsychology and mental health.

The recipient of numerous honors, including the 1987 medal of the Type Directors Club, Mr. Frutiger wrote many books. An anthology of his work, edited by Heidrun Osterer and Philipp Stamm, was published in English as “Adrian Frutiger — Typefaces: The Complete Works.”

His other fonts include Avenir, Centennial, Egyptienne, Herculanum, Iridium, Serifa, Vectora and Versailles.

As conspicuous as Mr. Frutiger’s work became, it was for its inconspicuousness, he said, that he hoped it would be known.

“The whole point with type is for you not to be aware it is there,” he said in an interview on the Linotype company’s website. “If you remember the shape of a spoon with which you just ate some soup, then the spoon had a poor shape.” He added:

“Spoons and letters are tools. The first we need to ingest bodily nourishment from a bowl, the latter we need to ingest mental nourishment from a piece of paper.”